Science works better when it’s taught as a story

For many people, school science felt like being handed a finished manual. You were told that the Earth goes round the Sun, that atoms have shells, that continents drift, that time slows down near the speed of light, and you were expected to take all of this on trust. You might have learned to solve problems or repeat definitions, but you rarely saw how any of these ideas were argued into place. The result is that science often comes across as cold, dogmatic, and oddly detached from common sense.

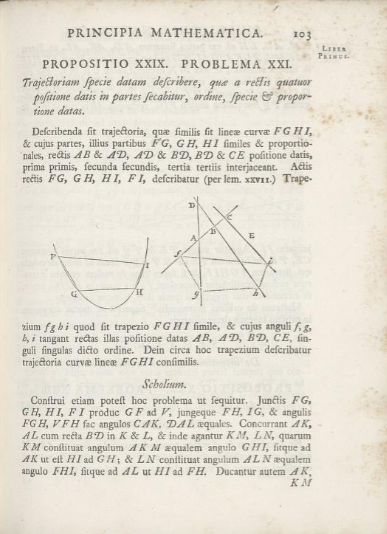

An alternative is to teach science as a story, not in the sense of fiction, but as a sequence of real attempts to explain the world, starting from early theories and moving forward as evidence piles up. Instead of beginning with Newton’s laws or the periodic table, students would meet Babylonian sky watchers, Aristotle’s ideas about motion and elements, Ptolemy’s epicycles, and the long struggle to make sense of planetary paths. From there they would see how Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo chipped away at those models, why Newton’s Principia was such a leap, and what problems it solved that earlier frameworks simply could not.

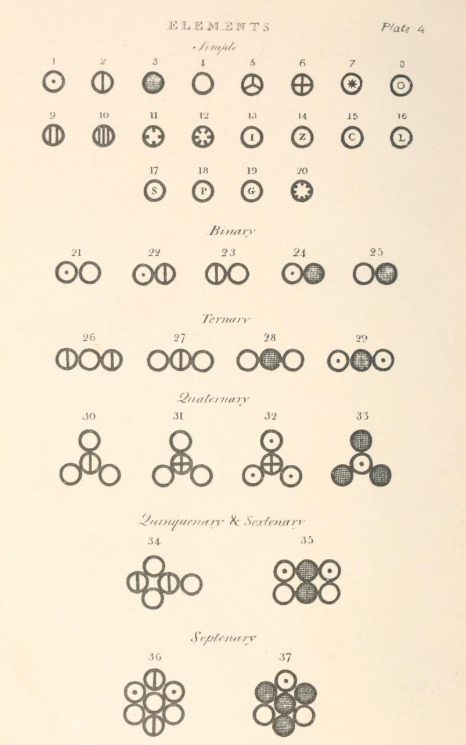

The same approach works across the sciences. In physics, students could move from Aristotle’s natural motion to impetus theories, to Newtonian mechanics, and later glimpse why relativity had to replace it. In astronomy, they could trace the path from geocentric models to heliocentrism, and then to modern cosmology. In chemistry, they might start with the classical elements, pass through alchemy, Dalton’s atoms, Mendeleev’s early periodic tables, and only later arrive at electron orbitals and quantum models. In biology, they could follow the road from Medieval classification to modern genetics.

None of this would be about mastering outdated theories. The earlier models would be simplified and used as tools for thinking, not as destinations. Students would read short, adapted extracts from works like the Almagest or the Principia, work through manageable bits of maths, and replicate classic experiments in scaled-down forms (the experimentation, hands-on aspect is crucial). What they would be learning, again and again, is how people reasoned with the evidence they had, where they went wrong, and what finally forced a change of mind.

This matters because so many modern scientific claims feel strange on first contact. That the Earth is a spinning sphere moving through space, that matter is mostly empty space, or that time and length depend on speed all sound implausible if they are presented as bare conclusions. But when students walk through the failed explanations, the mounting anomalies, and the steady improvements in measurement that led to these ideas, the conclusions stop feeling arbitrary. They become the best answers available to real problems. That experience makes scientific results feel intuitive rather than imposed.

This is also where the approach helps with today’s widespread mistrust of science. A lot of scepticism is not really about data; it is about authority. People are told ‘this is the science’ without being shown how that science earned its status. Teaching science as a historical process trains students to see why certain claims carry more weight than others. They learn to respect evidence, not institutions, and to understand why consensus forms when it does. That kind of understanding sticks far better than appeals to expertise alone.

There are practical worries, of course. This way of teaching takes time. Some early theories are odd and hard to get into. Teachers need broader training. Assessment has to focus on reasoning rather than rote procedures. And any change on this scale will meet resistance. But these are design and policy problems, not deal-breakers. With good scaffolding, old ideas can be introduced and then clearly left behind. Teachers, schools, and even teacher unions can be encouraged to opt in through higher pay, extra funding, and prestige attached to being part of a recognised high-quality track. Incentives work, and pretending otherwise helps no one.

Parents can be brought on board too if the benefits are made concrete. One powerful option would be to guarantee top-performing students from this system a free or heavily subsidised place in science degrees at university. That makes the value of the approach obvious and ties school learning directly to real opportunities later on.

Crucially, this does not water down science. It rearranges when different things are learned. Universities would still teach the modern theories properly and in full rigour. Students would learn the formal mathematics, the exact models, the abstractions of quantum mechanics, general relativity, thermodynamics, and modern biology, etc. The difference is that they would arrive with a well-built intuition for why those formalisms look the way they do and what problems they were designed to solve. The heavy maths lands better when the conceptual ground has already been prepared.

Teaching science as a story does not mean slowing it down or turning it into nostalgia. It means making it intelligible, human, and hard-earned. If students leave school understanding not just what science says, but how it came to say it, we should not be surprised if they trust it more, argue about it more intelligently, and find it far more interesting along the way.