Nature has a hidden side

Think about how we get to know people. You watch how someone acts day to day, how they deal with work, friends, small stresses, ordinary routines. Over time, you build up a picture of who they are. It feels solid and reliable, and you think you’ve got them figured out.

But then life throws something genuinely new at them — a crisis, sudden power, deep loss, extreme pressure — and they react in a way you never would have seen coming. But nothing about them has changed. What changed were the conditions. Certain ways of acting were always there, just never triggered.

I think that science works in much the same way with nature.

Science is extremely good at describing how the world behaves when it’s in its usual, stable moods. When systems sit in familiar ranges and don’t get pushed too hard, we can run experiments, compare results, and build up dependable patterns. Over time, those patterns harden into what we call laws of nature (I’ve written more on that here). In that sense, science gives us a very good read on how nature behaves when it’s comfortable. The trouble starts, though, when we quietly assume that this is the whole story.

Just as with people, what we really have is a record of how natural systems behave under the sets of circumstances we’ve actually managed to observe. Outside those conditions, there may be reactions and behaviours that remain hidden, not because they’re mystical or random, but because nothing has yet forced them to show themselves.

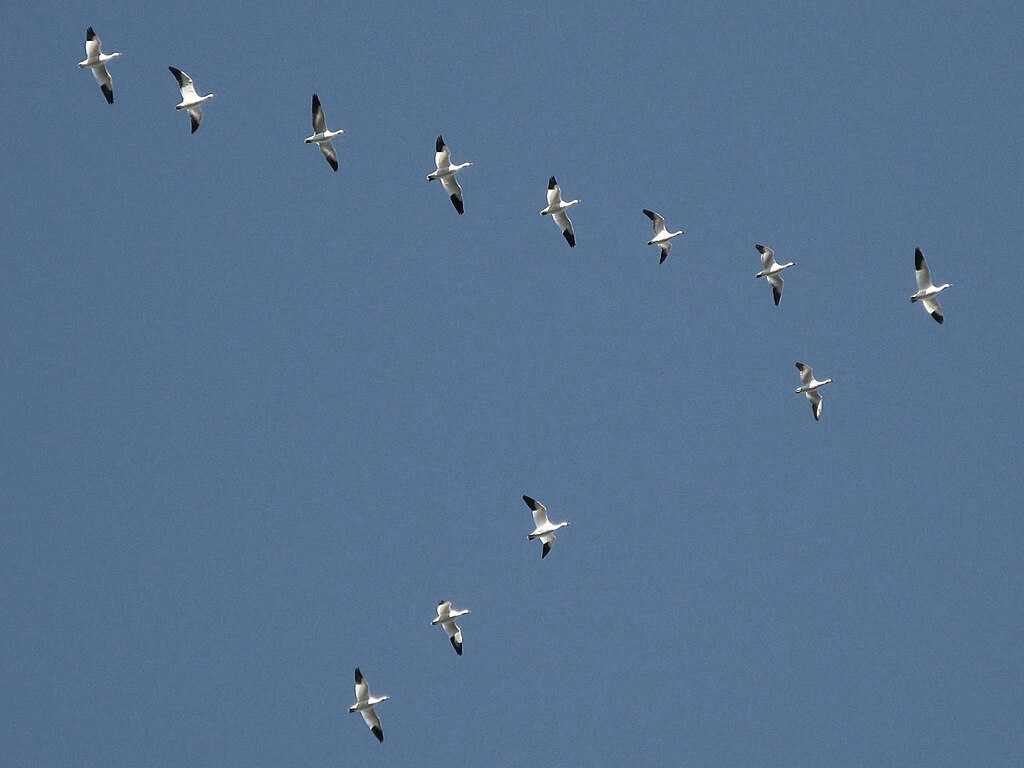

Thinking about this, I was reminded of the first time I saw geese flying in formation. Having lived near the equator my entire life, I’d never seen anything like it before. It was the summer of 2023, and I lifted my head one sunny afternoon in York, northern England. There they were, perfectly aligned in a shape like a carpenter’s square. I had never imagined animals could do anything like that, and yet there I was, seeing it with my own eyes. I know the analogy isn’t perfect (there’s nothing ‘extreme’ in travelling from the tropics to England), but the idea I want to convey is that nature is full of surprises, and we humans have to keep updating our beliefs as new observations come in. In a way, nature will always remain exotic.

It’s true that science sometimes does get glimpses of nature under unusual circumstances or under serious strain — violent collisions, astronomical events, early-universe conditions, sudden phase changes. But these are only samples, scattered points in a much larger space of possibilities. Seeing how someone reacts in one crisis doesn’t tell you how they’ll react in every crisis imaginable. In the same way, observing a handful of extreme or very rare regimes doesn’t give us a full picture of how matter and energy behave in all possible contexts.

What we’ve learned so far is therefore conditional. We know how systems act in the ranges we’ve been able to reach and deductively infer, and we can often make educated guesses beyond them, but we can’t be sure that no new behaviour will show up when the balance is disturbed in ways we haven’t yet encountered.

There are plenty of moments in the history of science where pushing systems into unfamiliar or extreme situations completely reshaped the picture. When Mercury’s orbit refused to line up with Newton’s predictions, it wasn’t a small tweak that fixed the problem but Einstein’s relativity, which only really shows its teeth at high speeds and strong gravity. When physicists looked closely at black-body radiation and atomic spectra — regimes far removed from everyday experience — classical physics broke down and quantum theory had to step in. At cosmic scales, the discovery that the universe is expanding, and later that this expansion is accelerating, forced a rethink of gravity, energy and the fate of the cosmos. Even in materials science, extreme cold revealed superconductivity, a behaviour no classical model had prepared us for. In each case, nature was pushed, or simply observed, outside its familiar comfort zone, and it responded in ways that made earlier ‘laws’ look like partial portraits rather than final descriptions.

Science doesn’t give us a full list of everything nature can ever do. It gives us a growing map of how nature behaves across the situations we’ve actually encountered, while countless other behaviours remain dormant, lurking in the background, never triggered and often beyond what we can even imagine. Most of these possibilities will probably never show up at all, because the conditions needed to bring them out are too rare, too extreme, or simply never realised. As a consequence, when new regimes do show up, that map sometimes needs redrawing, not because nature has changed, but because we’ve just stumbled upon another of its hidden moves.